This quiet, reserved and thoughtful corner of the year-round Yukon has gone to the birds this week, namely Arctic terns, the all-time migratory champions, not only of the bird kingdom but also the entire non-human animal world, including bugs and butterflies. You won’t believe what you are about to read but, first, you have to know why you are reading it:

Migration season is when fairweather Yukoners become Yugoners.

It’s migration season again, that transitory time of year during which northern Sundogs, often mistakenly called snowbirds, freeze in their tracks at the mere thought of anything white falling from the sky while offering half of their Canadian birthright to the Sun Goddess, if she will hold off the cold temperatures until Halloween, at least so they can safely get back to Margaritaville before they turn into permanent Rendezvous ice sculptures.

It’s the annual Canadian migration comedy during which many otherwise Yukoners become “Yugoners” until the snow melts and their beloved ruffled touri cash-cows return in May to refill their Jimmy Buffett bank accounts. They try to get as far south as they can to a place which still televises hockey, so they don’t get homesick at Christmas. But they don’t go very far away, usually Arizona, Mexico or Central America, much like the rest of the nectarine-sucking hummingbirds.

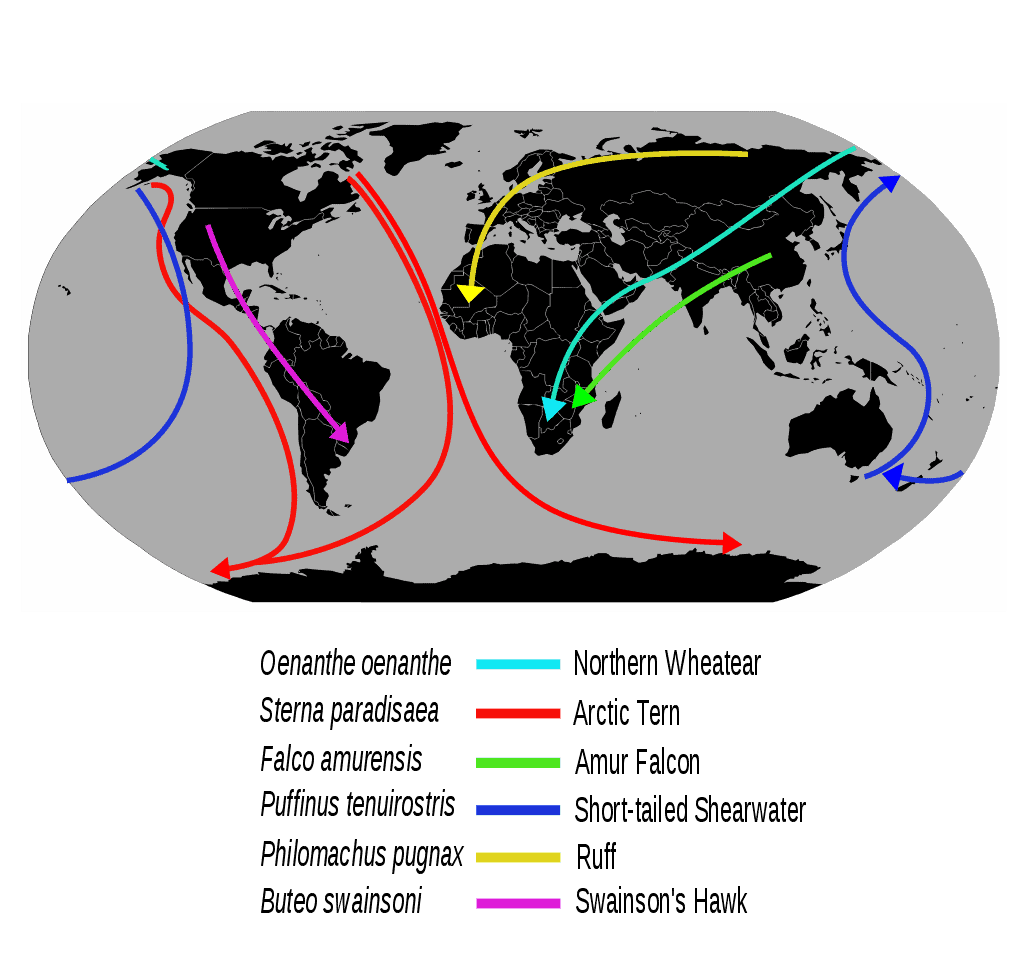

They’re all migratory lightweights against the exploits of the legendary Arctic terns that breed and feed in the Arctic and then follow the sun to the Antarctic, thus living their entire carefree 30-year lives without ever experiencing winter.

The shortest distance between the two polar circles is 19,000 kilometres or 12,000 miles, but when a tern chick banded in Labrador on July 23, 1928, was found in South Africa in November, a direct distance of 12,684 kilometres, it was considered a world record for the longest-known bird migration at the time. That was just the beginning of the elusive Arctic Tern’s rise to fame and glory.

In the summer of 1982, an unfledged chick (still nest-bound) banded in the Farne Islands, Northumberland, UK, in the northern summer of 1982, reached Melbourne, Australia, in October, just over three months out of the nest, a distance of 22,000 kilometres (14,000 miles), which was another new record (but not for long).

The invention of GPS satellite tracking, as well as lightweight transmitters weighing 1.4 grams, produced results and astonished researchers who had mistakenly assumed that terns migrated in a straight line. Wrong!

A 2010 study of 11 birds, banded in Greenland and Iceland, found that they averaged 70,900 kilometres (44,100 miles), with one bird setting the new roundtrip record of 81,600 kilometres (50,700 miles) which, when multiplied by their 15- to 30-year life spans, means it’s possible, indeed likely, that an Arctic tern’s lifetime migration mileage is roughly equal to three round trips to the moon.

In 2013, a half-dozen fledglings in the Netherlands were banded and individually tracked to Wilkes Land, Antarctica, with the following results: they averaged 90,000 kilometres (56,000 miles), with the champion bird racking up the new and current record of 91,000 kilometres or 57,000 miles.

That Superbird, the Muhammad Ali of migratory birds (if you don’t mind a boxing metaphor), travelled down the coasts of Europe and Africa, around the Cape, then went sightseeing to Australia after the others turned south for Antarctica about halfway across the Indian Ocean.

The Champ, whose gender is not known, cruised the entire southern coast of Australia to Melbourne, passing near Hobart, Tasmania, then swung past South Island, New Zealand, on the way to a relaxing and well-fed Antarctic summer.

If that’s not enough to impress you, the 2013 study also determined that Arctic terns don’t stop and rest on their wayward travels because they have learned how to lock their wings into a glide position and sleep while the prevailing winds carry them here and there—often at high speeds. Talk about a midnight joy ride!

The only time they are seen on land is when they are nesting in the Arctic. They eat fish and small aquatic invertebrates, which makes the curious among us wonder why they even bother coming to the Yukon, which is landlocked except for that small stretch of coastline on the Beaufort Sea north of Old Crow. They are a large and healthy species with estimates of a worldwide population of over a million, so it’s reasonable to assume they do some of their breeding in the territory and certainly a lot in Alaska, next door, with that massive coastline on multiple oceans and seas.

They were known as sea swallows at one time and were included in John James Audubon’s (1785–1851) Birds of America, a collection of 435 life-size prints—still a standard against which 20th- and 21st-century bird artists, such as Roger Tory Peterson and David Sibley, are measured.

Any common hummingbird, snowbird or sunbird can migrate to Mexico to avoid Canada’s Subarctic winters, but it takes a Superbird like the Arctic tern to spend summers in Antarctica.It’s too bad Anne Murray didn’t sing a song about them instead of snowbirds, which fly north to breed in winter (not the other way around). It’s a great nickname for confused Canadian Sundogs, but factually inaccurate. The true “Neverwinter Bird” from Yukon, Alaska, and other northern locales is the Arctic tern.