Nakai Theatre’s newest production, The River, promises to shine an unblinking light on Whitehorse by presenting voices that normally go unheard.

The “sprawling, episodic” play, co-written by Nakai’s artistic director David Skelton, Yukon artist Joseph Tisiga and Toronto playwright Judith Rudakoff, tells the stories of 12 separate characters in 60 scenes with no conventional narrative arc binding them together.

“Whitehorse is the connective tissue,” says director Michael Greyeyes. “When I read the script in development, I was pulled in immediately by the sense of place. Whitehorse runs through every page.”

And while Skelton hopes to take the play to other communities in the Yukon and outside after its local run, he says the decision to use recognizable local references was deliberate.

“People here will have a good time being able to recognize the names and recognize the places, but when it goes out, the specificity we are using will create a whole authentic world for people,” he says. “It will be universal, because we are making it specific.”

The River grew out of Rudakoff’s 2008 project to reflect “isolated, threatened communities” in various parts of Canada, Skelton explains.

The three writers recognized themes they wanted to follow up that lay outside that project’s parameters. They began with an extended walk through the city, where they observed “guys who were just sitting there, doing whatever,” Skelton says.

“We tried to figure out what would it be like if you had no place to go. How would you walk? What would your physical energy be if you didn’t have to be somewhere?”

From that starting point, the playwrights asked themselves, “How do you interact with people who don’t acknowledge you? You ask for a cigarette and someone just brushes right by you. You’re in a desperate situation and people just walk by.”

Among the characters that emerged over the next two years, Skelton says, were:

Paul, “a good-looking young First Nations guy” played by Telly James;

Archie (Wayne Ward), a man fresh out of prison, seeking “some kind of human contact in that brutal environment, and the brutal environment of living on the street”;

Joanna (Falen Johnson), a woman confronting “forces from outside her that come and do things to her, and she doesn’t have any control over them”;

Ruth, a single mother with alcohol problems, played by Vancouver actor Ayma Letang, originally from Whitehorse;

Helen (Barbara Pollard), who represents what Skelton calls the “superficial experience” of a tourist.

“It’s one of the things that defines the emotional landscape of Whitehorse, that the place where you live is on display, you see people who you know are just passing through, there are people who romanticize the way you live.”

Another character is an educated urban woman at mid-life who embarks on a “reckless, almost childish pursuit to find herself” in the Yukon, with problematic results.

Through the characters’ personal stories, The River takes an unflinching look at such issues such as racism, poverty, homelessness and dysfunction in the city, for which neither Skelton nor Greyeyes apologizes.

“As artists, we have a responsibility to tell these stories. We have a responsibility to the vulnerable people who are in society, to include them in the society,” Skelton says.

“I believe artists are educators, that we have a social responsibility to shine light on that which, most of the time we’re afraid to look at,” adds Greyeyes.

“Nakai has been committed from the very opening stages of this project to bringing and staging the voiceless: the people who, in all our cities, have a tendency of being ignored. What this play demands is that those people cannot be ignored.”

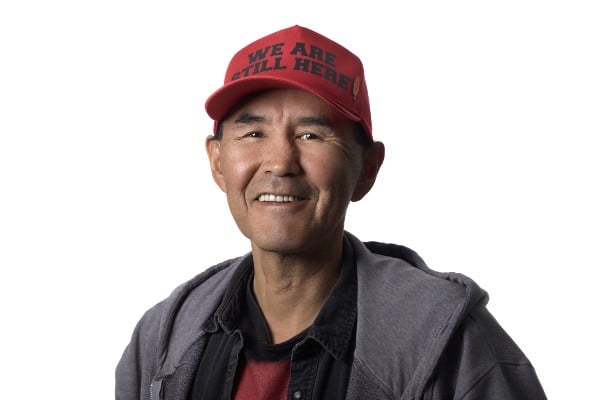

A Plains Cree with an extensive resumé as a ballet dancer, actor, choreographer, director, filmmaker and academic, Greyeyes says the issues confronting First Nations people here are not unique to Whitehorse.

“The cultures are specific unto themselves, but the experience of being aboriginal in Canada has a lot of parallels. A lot of things that are happening on the mean streets of Regina and the east end of Vancouver play out here as well,” he says.

As Nakai’s artistic director, Skelton has no illusions that one play will change public policy overnight, but he is hopeful that The River can help influence people’s awareness of those living on society’s margins.

To do that, the play presents the stories of people who are “fascinating, they’re funny, they’re interesting, they’re intelligent, they’re wry,” Greyeyes stresses.

“The ones that we couldn’t hear, for whatever reason; the ones that we didn’t hear, for whatever cause. Tonight, each night of the show, we are compelled to be there and we are compelled to hear their story,” he says.

By showing what makes the characters tick, without being polemical, Greyeyes says, the play “does what good art does: it breaks down barriers between people and reminds us of our common humanity.”

The River runs April 21 to May 1 at the Yukon Arts Centre Studio. Curtain time.