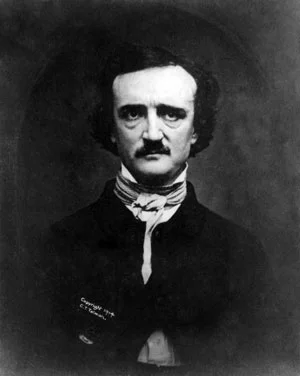

Very few writers throughout history have bonded with their subjects quite like Edgar Allan Poe and the Yukon’s territorial bird. His renowned 1845 poem, The Raven, a critical success, but financial failure, cemented man and bird into one entity to such a degree that it’s difficult to find a photo of the author without the ubiquitous raven, often perched on his head or shoulder.

Indeed, your humble researcher came upon over 200 images of Poe, most accompanied by one or several ravens. None showed anything resembling a smile to the point we cannot accurately confirm whether or not he had any teeth.

Although history has treated him well, Poe didn’t have a lot to smile about in his 40 years. His parents died when he was three and he was adopted by a strict, stern disciplinarian stepfather who hounded and haunted his childhood right into manhood. Nothing Poe could do would satisfy the ogre who massacred Poe’s teenage personality and turned him into an angry young writer with a gambling problem and the macabre attitude shown in his two biggest writing successes, The Cask of Amontillado and Murders in the Rue Morgue.

He also fell in love with his pretty first cousin, Virginia Clemm, when she was a little girl. He married her when she was 13, which was legal in the mid-19th century, though frowned upon by his respectable readers. They had heard only vague things about him before he wrote The Raven and became an instant celebrity and popular poet. The poem was published by 11 newspapers and magazines in the first month and netted Poe more than $100. It was a lot of money in those days, but it was all he ever made from what his wife disdainfully referred to as “the bird poem.”

She hated The Raven, his breakthrough effort, and developed bipolar disorder before succumbing to mental illness and dying of tuberculosis in 1847. Poe was crushed by her death and spent his last two years in a depressed alcoholic stupor. Although his death certificate said he died of “acute congestion of the brain,” a delayed autopsy later revealed he also had rabies.

Oblivious to him in his declining misery, history has decided he was the very architect of flowing morbid poetry and short detective prose and has given him the same kind of respect Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) received for his blockbuster fictions (Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer) in the 1870s. It is even theorized by some academics that Poe was the principle pioneer American fiction writer and Clemens his student. One perspective that’s certainly true is that Poe is more vibrant and readable today than is Twain, whose prose is badly dated and tough on the eyes. To wit:

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before— … Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Both Rimbaud and Baudelaire were devoted Poe disciples.He was one of the first authors to focus primarily on the effect of style, flow and structure in a literary work rather than content. It was art for art’s sake rather than a paycheque. Today, Poe is remembered as one of the first American writers to become a major figure in world literature.

Ravens have always been mischaracterized as both predators and harbingers of death and doom when they are actually neither. They are common, simple scavengers. As such, they are always present on battlefields and disaster sites, after the fact, to do their natural duty. There is nothing macabre or freaky about their makeup at all. Indigenous Raven myths always refer to them as playful tricksters, which is their true nature. The bad reputation they became saddled with over the centuries definitely didn’t begin with Poe, but it was certainly intensified by the gloomy American who garnered so much dark publicity. Indeed, had Poe selected any other scavenger such as a vulture, buzzard or eagle to tap, tap, tap on his windowpane, ravens would have enjoyed a far more carefree and playful reputation.

The macabre came from Poe’s dark, depressed nature and not the typical raven’s sunny disposition. Combined as they were with Poe’s protagonist, who was contemplating suicide over the loss of his lover named Lenore, the raven had to utter, mutter and stutter something continuously and it had to rhyme with her name.

And thus quoth the raven forevermore, “Nevermore.”

That made it one of the greatest poems ever written and a fine tribute to our beloved and revered territorial bird … at least, in the eyes of one card-carrying Yukon myth-checker.

THE TOWER RAVENS OF LONDON

Next time, we’ll discuss an ancient raven myth rumoured to have been started by King Arthur, himself a mythological figure, which is still intact today, and which was a major concern to Winston Churchill during World War II. It may surprise some to learn the psychological role ravens played in assisting the British Bulldog in the defeat of the Nazis and fascists.

Poe Bibliography

POETRY

Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827)

Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (1829)

The Raven and Other Poems (1845)

Eureka: A Prose Poem (1848)

FICTION

Berenice (1835)

Ligeia (1838)

The Fall of the House of Usher (1839)

Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839)

Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841)

The Black Cat (1843)

The Tell-Tale Heart (1843)

The Purloined Letter (1845)

The Cask of Amontillado (1846)

The Oval Portrait (1850)

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1850)