There’s a lot more than gold in them thar hills and creeks in the Klondike. Aside from all kinds of other minerals that just don’t seem to occur in large enough quantities to be of commercial, there are bones that have helped to tell the tale of the region’s pre-history.

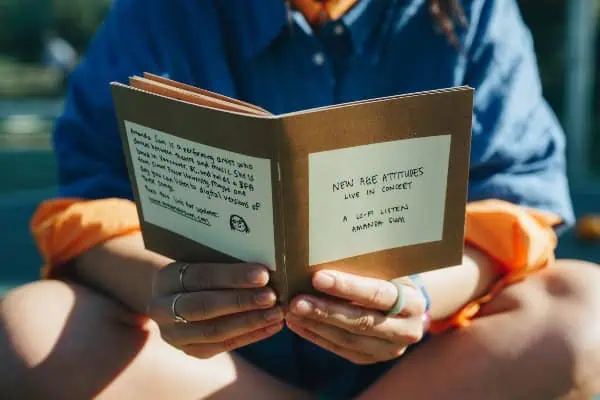

Miners have been finding bones and fossils in the Klondike as long as there have been miners and the Yukon government’s 2011 publication of Ice Age Klondike (by Grant Zazula and Duane Froese, 36 pages, from Yukon Tourism and Culture) tells this story in an engaging text augmented with lots of relevant photos, maps and drawings, all packed into a well-designed little book that is more than just another tourist brochure.

It’s more like a mini version of a coffee table book in its impact.

The images are a mix of historical and modern photographs that emphasize the interrelationship between the mining community and the paleontologists.

Many of the findings from the Klondike have ended up in Ottawa. A good many of them support the existence o the Beringia Interpretive Centre in Whitehorse.

There is even a sizable display of Klondike material at the Royal Tyrell Museum, the facility named for Joseph B. Tyrrell, the Canadian geologist, cartographer and mining consultant who discovered the bones of the dinosaur now known as albertosaurus in 1884 while doing geological work around Drumheller, Alberta, where the museum is now located.

Tyrrell later came to the Klondike, devoted himself to mining and then moved on to become the mine manager of the Kirkland Lake gold mine for many years. There is a plaque honouring Tyrrell in Dawson, and his house on Seventh Avenue is currently for sale once again.

But this column is mostly about the bones, which excited national and international interest as early as the turn of the 20th Century. By 1904, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris had sent a team to the Yukon, prompted by reports by Canadian geologist R.G. McConnell.

In short order, we also hosted visits from the U.S. Biological Survey, the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Institution, all of which were excited by the magnitude of the finds being dug and sluiced out of the ground by the miners here.

The book indicates that the sum the work completed here, much of it guided through the 1960s and 70s by Dr. C.R. (Dick) Harington on behalf of the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, has enabled scientists to map changes in the animal population of the region over a period of 2.6 million years.

The authors have been very careful to point out that nearly all of this material and information would never have come to light without the work of the miners in the region of the Klondike—a region which for these purposes stretches out to Thistle Creek and the Sixty Mile River.

Over the years I have been present at and reported on a number of citations and awards presented to hardworking miners who have saved up their finds and turned them over to the scientists.

The Yukon finally got around to forming its own Palaeontology Program in 1996, and the passage of the Yukon Historic Resources Act in the same year means that all fossils and bones found in the territory have to be turned over to the government, but miners were doing it well before that date.

For a look at a side of the mining industry that you might note have considered, this book is a worthwhile read. It’s available from the Yukon Palaeontology Program and from the government, and it can even be read online at www.tc.gov.yk.ca/pdf/ice_age_klondike.pdf, but I think it’s worth having in hard copy myself.

After 32 years teaching in rural Yukon schools, Dan Davidson retired from that profession but continues writing about life in Dawson City.