One of the fun things about fermented foods is passing on bits to others, knowing they will grow and spread like a great idea. It required a bit of a mental leap to go from creating my first ferments to seeing this possibility, kind of like going from growing your own lettuce each year to saving your own seed and swapping with your neighbours; it’s taking things to the next level.

I probably began with dairy, begging a spoonful of yoghurt from a friend to start my own and now after experimenting in all kinds of other departments I’m back on the cheese wagon.

I’ve been making cheese with local milk for a few years now, mostly goat as I can get it, and have had niggling doubts about the freeze-dried cultures I began to use early on. Each is a specific strain or small collection of strains of bacteria that develop particular flavours and textures and most cheesemaking books, even for the amateur, will call for certain combinations for each cheese.

My self-sufficiency nerd has wailed, but what if that culture is no longer available? What then? And the inevitable question arises, what did people do before they could go on the internet and order up a package of freeze dried mesophilic bacteria?

So far my only responses have been to use old bits of cheese to inoculate new batches (with some, albeit limited, success), or to scrape the inside of other people’s cheese-forms when they aren’t looking. That approach is going to require more field trips than I can afford if I want to seriously diversify.

Well, my angst has been resolved courtesy of David Asher, guerilla cheesemaker, who visited the Yukon a few weeks ago.

To back up a bit, cheese happens when milk essentially “goes off” in the right sort of way; meaning it achieves the conditions that favour a certain contingent of the microbiotic community already present in raw milk, or added in to pasteurised milk.

Asher is a proponent of using kefir (a type of symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast that live as a glob suspended in its feeding medium, milk) to de-pasteurise or enliven store-bought milk. The finished product is similar to yogurt, the main functional difference being that the culture responsible for the transformation is not eaten with the final product, but instead the kefir grains are removed and added to fresh milk to continue their transformative work.

The cool thing that was news to me is that there are so many different organisms within the kefir grain that, by varying the conditions, Asher has been able to replicate the entire cheese using this one starter culture. A culture that Asher proudly assures his students descends from the grains discovered in central Asia thousands of years of ago – beats our centenarian sourdoughs by a fair shot!

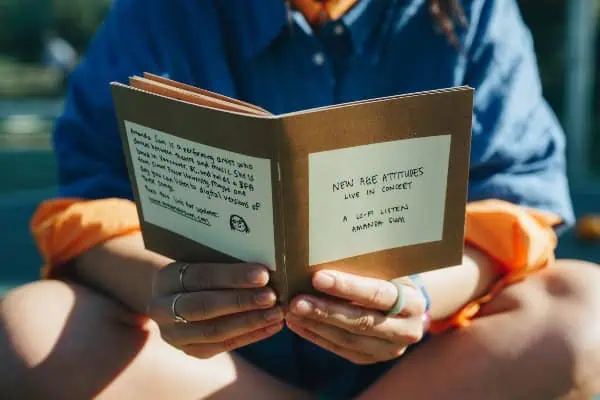

Asher gave an evening workshop in Mount Lorne during his Yukon visit as a precursor to a full-weekend event in Dawson City, and both were well-attended.

Every participant in either course I’ve spoken to since has been inspired by the cheesemaker, whose mild manner of speaking belies a passionate conviction in the need to reclaim our food traditions. I certainly feel better equipped to carry on my experiments.

I am particularly looking forward to continuing my exploration of aging cheese – friends ask how I can stand to wait instead of gobbling up each cheese as soon as I make it, but I seem to have the opposite problem. I am so curious to see what will happen next (I’m not a very goal-oriented cheesemaker), that I am likely to do no more than nibble on the way because I want to discover what the six-month old cheese tastes like at a year!

For those keen to see what others are doing with cheesemaking, check out Mount Lorne’s Ingestible Festival in August – cheese has its very own category. Whey cool.