International Women’s Day happens March 8 in countries around the world. Themes vary by country. For 2022, the Government of Canada chose “women inspiring women.” I caught up with two of the artists who were finalists for the Yukon Prize for Visual Arts—Krystle Silverfox and Veronica Verkley—to talk about who inspires them in art and in life.

Verkley makes animals who are remarkably lifelike even though they’re made out of unusual, often non-organic materials. The creatures inhabit spaces so convincingly, we immediately feel an empathy for them. Our fates seem profoundly intertwined with theirs. This is particularly true of “Suspended Animation,” a life-sized horse made of steel, plastic, rubber and other industrial materials. Weighing roughly the same as a real horse, the prone animal requires 10 humans to hoist it to standing where its movements are uncannily horse-like. At some point, those 10 humans realize that they’re going to have to let the horse go and watch it crumple to the floor.

It’s no surprise to learn that one of Verkley’s inspirations is French-American sculptor Louise Bourgeois. Canadians would know her best as the artist who created the monumental spider, “Maman,” who stands outside of the National Gallery in Ottawa. As terrifying as the giant arachnid seems, she is actually an ode to the artist’s mother. “Maman” even has a sac of eggs on her underbelly. She is therefore a sympathetic creature, just like Verkley’s horse.

Verkley admires Bourgeois’ independence and her ingenuity in the way she made her art.

“She was just a powerhouse in terms of doing her own thing and really expressing herself through her work and just so prolific and so amazing,” Verkley says. “Every time I see her pieces I think ‘Oh, I wish I’d thought of that.’ I just love everything about how she made things, the decisions she made in the way of making that I really, really love.”

The second artist that Verkley names as an inspiration is American sculptor, Chakaia Booker. Booker uses old tires and stainless steel to make monumental non-representational public sculptures as well as smaller studio pieces. Verkley says she thought a lot of Booker’s work while making “Suspended Animation.” The twisting and manipulation of industrial materials is characteristic of both artists’ work.

Verkley recently left the Yukon to live in B.C., but she will always remember her long-time home in Dawson, where there are “so many strong, capable, no-bullshit, skookum women that were and are so inspiring.” Just a few of the folks Verkley mentions include visual artists Jackie Olson, Faye Chamberlain and Claire Falkenberg; Aubyn O’Grady, who runs the School for Visual Arts (SOVA); Wendy Cairns, who owns Bombay Peggy’s; and SOVA instructor Nicole Rayburn.

All of these women and many more are inspirational to Verkley. Women in Dawson City, she says, “are living their best lives.”

Soon after Verkley left Dawson, another Yukon Prize finalist, Krystle Silverfox, moved to town. She is teaching at SOVA, where Verkley was also an instructor for many years.

As a visual arts undergrad, Silverfox attended the University of British Columbia (UBC). One of her instructors was Dana Claxton, an Indigenous artist who “has been a huge inspiration to my work,” Silverfox says. She had just finished a bachelor’s degree in gender, race, sexuality and social justice, and appreciated Claxton’s incorporation of feminist theorists (like bell hooks and Simone de Beauvoir) into the class.

“She’s just so inspiring … Just talking to her for five minutes can be very uplifting. It feels like someone’s on your side and they’re very supportive and they want the best for you. That’s something I really appreciate and that’s something, as an art teacher, I want to do for my students as well.”

Silverfox says she “lucked out” having Claxton as an instructor in a male-dominated faculty.

“Just having a female-identified Indigenous artist working at UBC teaching theory—which, I love theory—was just, for me, was so inspiring. Someone I could look up to and be like ‘yeah, I want to be like her.’”

Claxton’s supportive, encouraging approach to teaching has also rubbed off on Silverfox.

“Instead of telling [my students] what I want to see, I want to encourage them to explore what they want to do. I’m just the facilitator kind of thing.”

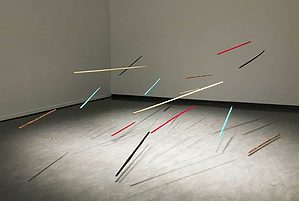

The second person who Silverfox names as inspiration is Jeneen Frei Njootli, an interdisciplinary Vuntut Gwitchin artist currently living in Old Crow. They were a Sobey Art Award Finalist in 2018.

“All of Jeneen’s work is just gorgeous aesthetically,” Silverfox says. “Even if it’s sound work, it just has something beautiful about it. I’m very inspired by their work.”

Silverfox’s work is also beautiful. “All That Glitters is Not Gold…” features a Hudson’s Company Bay blanket (a nod to the HBC’s Fort Selkirk) hung in a frame, which mimics hide tanning. At the bottom of the piece, pennies are scattered on the floor, referencing copper mining. Silverfox, who is Northern Tutchone and a member of Selkirk First Nation, combines these materials to incorporate concepts of “identity, land and resource extraction” in a powerful piece with a quiet, balanced beauty.

I imagine that SOVA students who now attend Silverfox’s classes and who once attended Verkley’s, have found inspiration in these artists. Verkley’s practice requires, among other things, knowledge of how to use power tools. As an instructor, Verkley tried to help students feel comfortable using them as well. Without making a big deal of it, Verkley aims to normalize experimenting with tools and industrial materials, and making complex, large-scale sculptures.

Silverfox, too, has an inspiring approach to her practice. Part of that inspiration is the way she sees gender as a fluid concept, where artists can have whatever kind of practice they want.

“As an artist, as an Indigenous artist and as an Indigenous feminist, I think about gender as being very fluid and something that can, and for a lot of people does, change in different spaces and times of their lives … I realize a lot of my art is beading and textile work, but also I do carve so I I don’t feel like these preconceived notions of what a female or male Indigenous artist should do really affect me that much. I just do what feels good for me.”