Centred in one of the Yukon Arts Centre galleries, as if on a page, stand 10 plinths and a “desk.”

Imagine the other 10 plinths stuck together without the spaces between them – that is the desk. A clear-handled, wide-edged brush; a small oriental slate ink stone and a block of ink to grind on that stone all wait on the desk.

On each of the square plinths stands a stack of white paper, the same size as the plinth in cross-section. One-thousand sheets make up each stack. Ten plinths, 1000 sheets each – 10,000 sheets awaiting S’s.

As calligrapher Owen Williams points out at his artist talk, the combined height of paper and plinth equals exactly five widths of paper.

These kinds of obsessively mannered spacing decisions are often an important precursor to the art or fine craft of calligraphy.

But these are only the initial pencil lines on the page.

The real content of S: 10 000 Variations, is the performance of writing. The gallery is both page and stage.

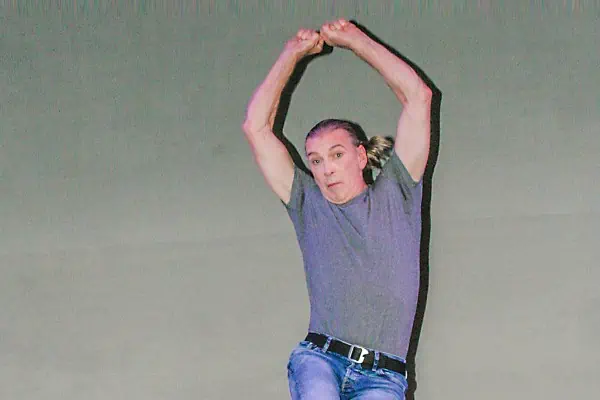

Each day, Williams will be taking the pages off the plinths and writing S’s, one per page. Non-calligraphic viewers might not know that an S is a kind of choreography of three gestures with prescribed shapes and directions.

Williams will vary these gestures as he explores the S.

Williams is interested in “gesture as a mode of communication” and calls calligraphy “the art of gesture.”

Letterforms are conventionalized in order to communicate clearly to their readers, but they’re a subset of all human gestures, which “communicate enormously and often have conventionalized meaning”.

Consider the handshake, the hug, flipping the bird – three conventionalized gestures that carry unmistakable and often unambiguous messages.

As Williams writes, he will muse on the relationship of his gesture, to the mark being made. “The show is about me writing,” he says, when viewers suggest they’d like to see the S’s he makes posted somehow on the walls.

At the end of each day, he ties up his day’s work, with string, and returns the bundle to the plinth.

Williams observes that he has “hijacked” the Yukon Arts Centre and its contemporary art context toward his own interests in calligraphy, which has different preoccupations.

A selection of the texts, which inspire his ideas, lies open inside a glassed-in box at the entrance wall to his exhibition.

He calls it a “cabinet of curiosities,” aware that the obsessive questions of Classical vs. Romantic aesthetics and the democratic connotations of sans serif typeface represent an “alien culture” to most viewers.

(Although most of us write at least one S a day, we don’t think about it that much.)

This is important: Williams is not demonstrating. He is performing.

The Yukon has a strong culture of artist demonstrations. There are few places in Canada with as many opportunities for artists to do their work in public, connecting and talking with the public.

But in this show, Williams is performing.

While he writes, he will not speak – no more than a dancer would. The gesture of writing is itself the content, not an illustration to an explanation of his practice.

Each day Williams will post a running total of the number of S’s he has written – the “variations to date” – on ArtsNet. He will keep going until he’s done 10,000, or until he flies to Vancouver on Feb. 19.

The overall installation will remain in place until March 15, hopefully with 10 bundles of 1,000 S,s … each topping each of the 10 plinths.

Little black drops of ink dot the “desk” when I arrive at noon on Friday. The wet brush lies clean on the ink stone when I arrive on Saturday at about 4:30.

Williams works tidily. Sadly, I missed seeing him actually write both days.

To see him write, time your visit between 1:30 and 3:30.

However, the voluble calligrapher will fountain aesthetic theories if you catch him before he starts or after he washes his brush for the day. At the latter end of the day, odds are good you’ll get to see the ink drying on some of that day’s variations on the letter S.