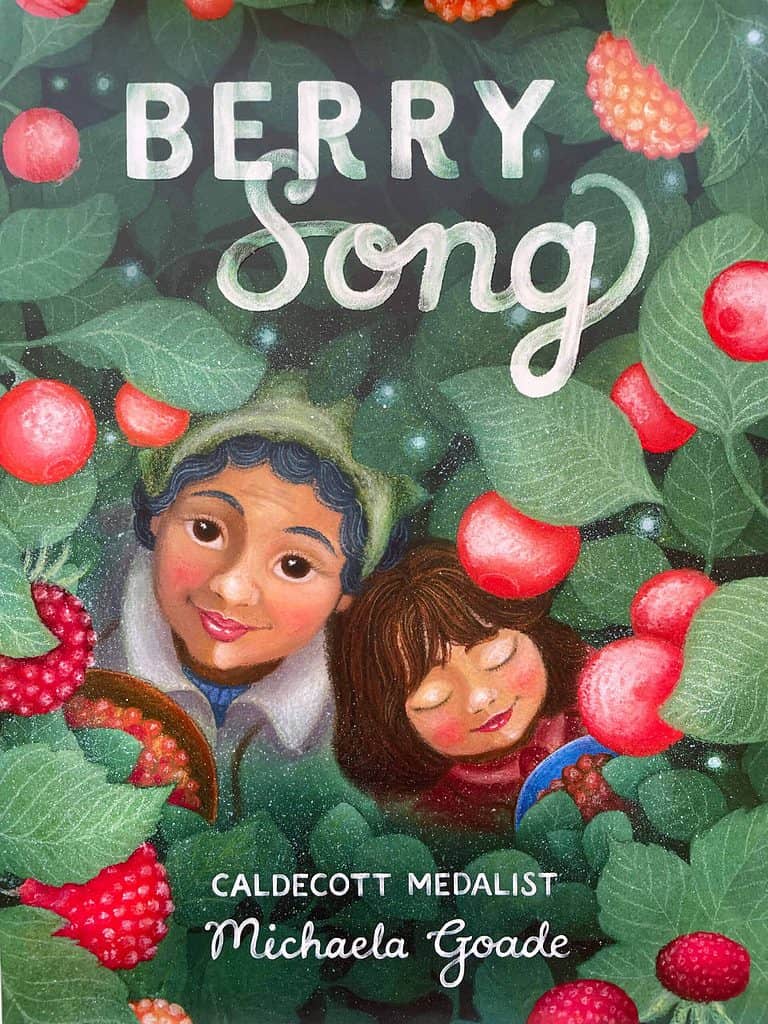

This past July, a beautifully illustrated and enchanting children’s book called Berry Song was published. Written by Michaela Goade, a member of the Tlingit and Haida tribes from Southeast Alaska, it tells the story of a young girl and her grandmother picking wild berries and connecting with the land. It’s Goade’s first self-authored picture book, but she previously illustrated several award-winning and bestselling children’s books including I Sang You Down From the Stars, by Tasha Spillett-Sumner; and We Are Water Protectors, by Carole Lindstrom (for which Goade won the prestigious Randolph Caldecott Medal and became the first Indigenous artist to do so).

Berry-picking season has always been a favourite time of year for me, ever since I was a little girl. Growing up, I remember learning about the different wild berries from my mom. The sweet wild strawberries were always the first ones to appear in summer. Soapberries would start to turn red in July and were a favourite treat for the bears after a springtime diet of dandelions, willow catkins, roots and grasses. Eventually came the Saskatoons, which I always liked to eat fresh and personally preferred to the slightly sour wild blueberries growing near Fraser. Saskatoons felt like loyal friends—filled with sweetness and always found not far from home.

Wandering through the forest or up into the mountains, we’d come across juicy mossberries (a.k.a. crowberries) and tiny bilberries and the occasional delightful nagoonberry. The wild raspberries were always ripe before the ones in the garden and had a much stronger flavour than the domesticated varieties. Black currants could sometimes be found hidden near streams and often revealed their presence by the unique fragrance their leaves released into the air as we walked by.

Later in the fall, cranberry picking made for a wonderful way to reconnect with old friends; afternoons were spent kneeling among the berries, catching up after a busy summer and before the cold winter winds would force us all to spend more time inside.

The last berries of the year were usually the rosehips, softened by a few frosts and always a favourite of mine because, if you found a patch of big ones, you’d have a full bag in no time. Even if the first snow blanketed the forest floor, rosehips were still easy to spot.

Those memories that I have—of berry-stained hands, a full belly and time spent with good friends out in the forest—are some of the happiest ones I have. To me, finding a good berry patch always seemed like magic. In so many parts of the world, if you want to harvest something, you first have to work the land, plant something, take care of it … and only then will you be rewarded with something to eat. Most of the world’s cities are filled with food deserts where very little grows and everything has to come from the supermarket. But here, in the North, we’re blessed with so much abundance that gives itself freely to us and asks only that we respect and care for the land, in return.

It’s that abundance and connection with the land which Michaela Goade celebrates in Berry Song. The young girl in the story gathers salmon from the streams, herring eggs from the ocean, seaweed from the beach, and berries from the forest and, all the while, her grandmother shares with her ways to deepen her relationship with nature and reminds her to show gratitude for the gifts that they’re receiving.

“We speak to the land as the land speaks to us,” her grandmother says. “We take care of the land as the land takes care of us.”

Goade’s own love of the land shines through in her stunning watercolour and mixed-media illustrations. Little forest creatures are hidden among leaves and branches, and hints of the young girl’s Tlingit ancestors can be glimpsed behind trees. Her paintings seem to glow from within, pulling us into a magical, lush world of plants and water and berries. Everything is alive and filled with spirit: the ocean waves, the temperate rainforest and the clouds hanging low with rain.

The last two pages include a note from the author; and there, Michaela Goade says that, for her, berry picking is medicine. I agree. Picking berries brings me into the present moment in a way that few other things do. It makes me aware of my surroundings, opens my eyes, quiets my mind and connects me with the earth below my feet and with the people around me. I think, somewhere deep inside of us all, we connect to an ancient remembering when we go out into the forest. Our ancestors, no matter where they were from, most likely gathered berries, too, cherishing their sweetness (probably even more than we do now) in a time before refined sugars.

Transforming Mother Earth’s sweet gifts into jams and muffins, pies and crumbles, always makes me think of my mom. Sometimes I wish that I had paid more attention when she taught me these things, years ago, and sometimes I still have to call her to ask about the steps I’ve forgotten. There’s something about the things we make from wild berries that begs to be shared. Gifts from nature become gifts between friends: bags of cranberries shared with our Elders who can’t go out and pick anymore, blueberry muffins enjoyed over a cup of tea, or a few jars of jam exchanged between friends and family. The natural world nurtures us and, in turn, we are given the chance to nurture others within our community.

Berry Song invites us, young and old, to live in reciprocity, to be joyful, to say Gunalchéesh, to not take more than what we need, to learn sustainable harvesting practices, to share the forest with our human and non-human relatives, to listen to the land and to not take what we’re given for granted. It asks us to coexist in respect and balance with the land. The final lesson that the grandmother in the story shares with her granddaughter is this: “We are part of the land as the land is a part of us.” We come from the land and we go back to the land. We are not separate from it, and it’s our responsibility to care for it and protect it. It’s a beautiful message shared within the deceivingly simple format of a children’s book.Berry Song is a story for us all.