The Cold Facts

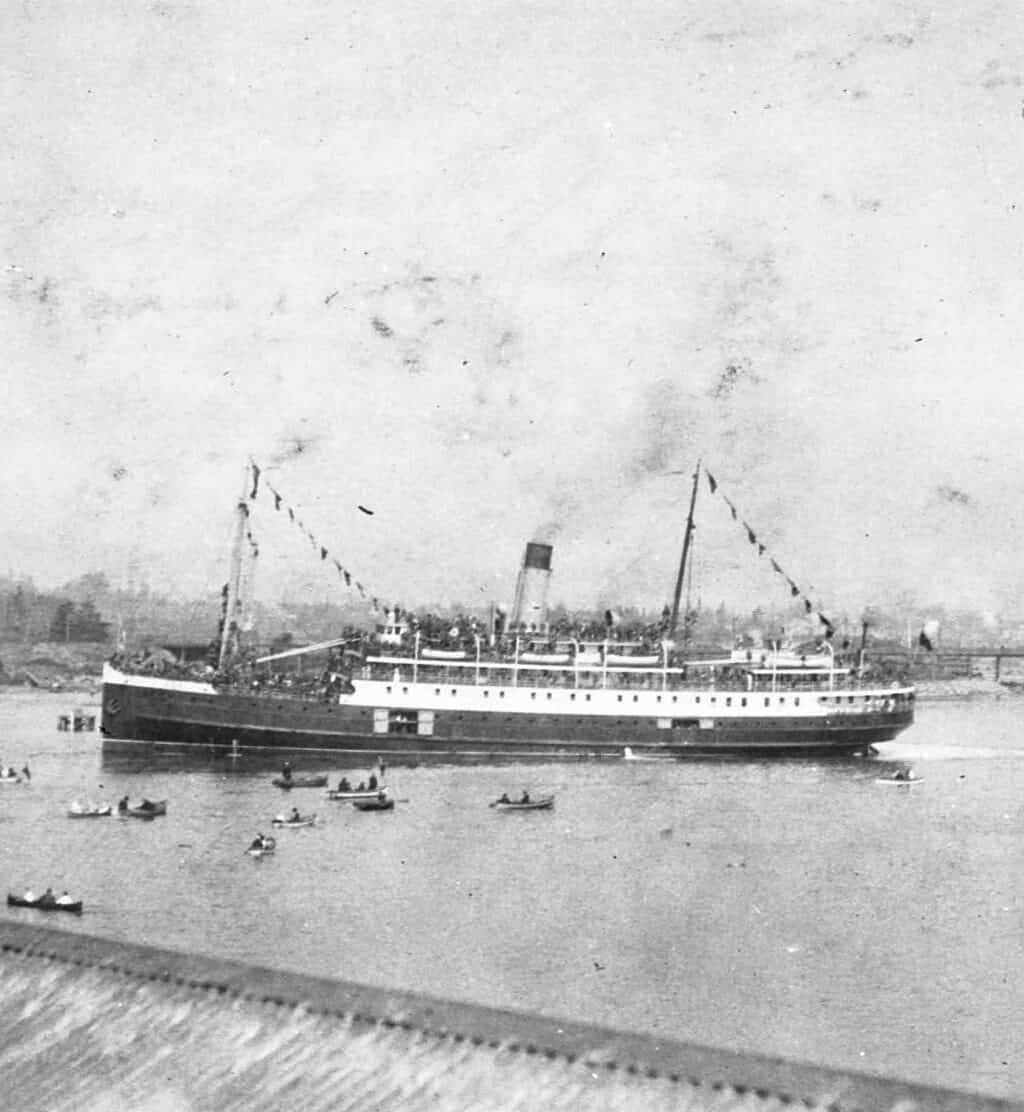

On October 23, 1918, at 10:10 p.m., over three hours later than scheduled, the CPR vessel S.S. Princess Sophia (So-PHY-Ya) piloted by Captain Leonard Locke, departed Skagway with at least 353 passengers and crew, the exact number unknown because stowaways, workaways and others were not recorded. There were also 14 horses on-board and several dogs, including an English Setter that swam to shore covered in fuel oil and survived.

On October 24, at 2:10 a.m., under full power in a north-wind whiteout blizzard, the Sophia ran aground on Vanderbilt Reef, a little over halfway to the scheduled first stop, which was Juneau.On Oct. 25 at 5:20 p.m., at the height of the rising tide, the bow of the Sophia floated up, spun the vessel 180 degrees and she slipped off the reef into deeper water as the last message was sent: “TAKING WATER AND FOUNDERING. FOR GOD’S SAKE, COME AND SAVE US!”

The watches on the victims read 6 p.m. There were no survivors and none rescued, despite a large flotilla of heroic boats and ships from Juneau that spent the whole day circling the reef trying to figure out how to get the humanity off of the doomed ship. It was Captain Locke’s call and he felt certain the ship could make it through the night, postponing the rescue until the weather improved, so he sent the rescuers back to safe harbours.

When they returned, on the early morning of October 26, there was nothing visible above water but one mast of the Sophia.

Eighty-seven of the deceased were summer employees of the WP&YR (White Pass and Yukon Route) river division, including masters and captains, and 126 were residents of Dawson City when the population was roughly 800, which equates to 16 per cent. Some were leaving for the winter, some were leaving forever; but none ever returned, which caused editorials predicting the Klondike’s ultimate demise at the age of 20 which, of course, never happened.

“Sophia is a Greek derivative meaning ‘divine wisdom.’”

Ten Cold Mini Memorials (ages in 1918)

1. George F. Mayhood, 60, from Napanee, Ontario, went to California when he was 17 in 1875, and was 40 when he reached Dyea in 1898. He survived the Sheep Camp avalanche of April 4, 1898, on the Chilkoot Pass (with a broken leg), which killed over 60, most of them young men from Washington, Oregon and California, the early first wave of the stampeders. He became a provisioner (of dry goods) in Dawson, then followed the “echo booms” to Nome, Chatanika, Fairbanks, Tanana, Iditarod, and had a cigar store and finally a pool room in Ruby in 1918. He loved the North, but his wife and kids did not so they were following the “lure of the South” and moving back to California.

2. Thomas Turner, 30, Stanford graduate and assistant dredging superintendent for Yukon Gold Company in Dawson, got drafted when the U.S. entered the war and was on his way to San Francisco to enlist.

3. Capt. James “Cap” Alexander, a Boer War veteran, spent a decade working his ground at Engineer Mine, on Tagish Lake, in the summers and spending his winters in financial centers, such as Vancouver, Toronto, New York and London, talking to potential partners or buyers. In 1918 he was offered over $1 million by Mining Corporation of Canada (MCC), to sell out, and boarded the Sophia with his young wife, Louise, and three of MCC’s employees, to conclude the negotiations in Vancouver and Toronto. It is believed the English Setter that swam to shore and survived was his.

4. William Scouse, 56, born a Scottish coal miner who drifted west and found his way to the Yukon by way of Pennsylvania, Kansas, Washington, Nanaimo and the Queen Charlottes, arriving in the Yukon River valley in 1896, just in time for the Klondike. He was in the early local rush and made his fortune on #15 Eldorado, the richest gold-bearing creek in the world at the time. He married in 1902, built a mansion in Seattle and never spent another winter in the North. In 1918, he was still digging out $10,000 per season while holding mining claims and real estate worth $125,000. It was his habit to catch the last boats and ships back to Seattle every October.

5–6: Murray and Lulu Mae Eads, from Kentucky and Alabama. Both were 1898 Gold Rush veterans who never left Dawson until 1918. Murray got rich owning the Monte Carlo and Flora Dora dance halls and married Lulu Mae, who was one of his star attractions (the others being Diamond Tooth Gertie, the Oregon Mare, and Babe Wallace).

The wealthy Eads diversified in the war years, buying a distillery in Dawson and a bank in Seattle, but decided to move south in 1918. Lulu had nightmare premonitions of drowning in a shipwreck and carried over $5,000 worth of valuable jewels and nuggets in a leather gold poke around her neck, which was how they identified her body. They had 20 years of good luck, much fame and great fortune in Dawson, but their luck ran out on Vanderbilt Reef. It was well-known in Dawson that Mrs. Eads was the role model for the infamous “lady that’s known as Lou” in Robert Service’s most popular poem, The Shooting of Dan McGrew.

I’m not so wise as the lawyer guys, but strictly between us two —The woman that kissed him and — pinched his poke — was the lady that’s known as Lou. – Robert Service, The Shooting of Dan McGrew

Lulu’s former co-worker, known as the Oregon Mare (real name: Edine Neil), was also going out that winter but had not booked on the Sophia.

7. Walter Harper, 27, son of Arthur Harper, co-founder of Dawson City, with Joe Ladue, and known as a “Father of the North.” He was from northern Ireland and fathered Walter with a native woman when he was 70. The young man was considered a kind of Superman in the bush and was in the first party to climb Denali, then called Mount McKinley, the highest mountain peak in North America. He married Frances Wells, a nurse from Philadelphia, in September, and they booked a birth on Sophia to take them south so he could begin medical studies, with the goal of becoming a doctor in Alaska and working with his mother’s people. But first he was going to enlist if Kaiser Bill still wanted to fight. He never got the chance to do either.

8. Bill O’Brien and his wife, Sadie, had five energetic and popular children between two and 14. He was a prominent Liberal who was seated on both the Dawson town council and the territorial legislature. He was also an Irish baritone and part-time entertainer who was the headline act at the annual “Sourdough Dance” in Skagway the night before Sophia‘s departure. The last song of that joyous bon voyage soiree was “Home Sweet Home.”

He didn’t resign his political posts but told old friends he was interested in joining his father-in-law’s manufacturing company in Detroit.

9. “Cap” and Louise Alexander left their eloquent, though somewhat potty-mouthed parrot, Polly, with the owners of the Carcross Hotel for temporary safekeeping, which became permanent when she became an orphan. Polly entertained hotel customers for the next 50 years with her bad manners and rude comments, became a local celebrity and attracted a large crowd for her funeral and burial. In her own unique way she became a living reminder of the Sophia tragedy.

10. Over 80 strong young men, the last draftees from the various mining camps in central Alaska, were on their way to Seattle to enlist and had reservations for the Sophia, which was badly oversold so they got out of Skagway on an earlier ship, the S.S. Prince Rupert, on the 23rd, and lived to see the war end 19 days later. They had to be the luckiest draftees of WWI.

There were also mayors on-board the Sophia, from Eagle and Chatanika, and many prominent government officials from all over the Northland, but the majority of the passengers were successful gold miners, who went out every winter; and seasonal workers the locals called sparrows, mostly hard-working young men who came north every spring and were barely noticed all summer—like sparrows—until they left.

According to the official passenger roster, the intended destinations of the Sophia‘s 278 paid customers were:

1. Seattle – 151

2. Vancouver – 85

3. Victoria – 16

4. Prince Rupert – 23

Clearly there were more Americans on-board than Canadians (151–124), and when you add stowaways, workaways and “migrant Chinese workers” to the official roster, a best guess is that 365 human lives were lost on Vanderbilt Reef, but nobody knows the exact number for certain due to the lazy and hazy nature of maritime accounting. The Sophia‘s log book went down with the ship and was never found. It’s not even known which of the four possible pilots was at the controls when the Reef was struck, but it was almost certainly either the Master, Locke, who was 66; or his first officer, Jeremiah Shaw, 36. Either way, it was Locke’s responsibility.

The Cold Calculations

The villain in this sordid tale of seawater woe is misnamed because Vanderbilt Reef is not a reef at all. It is actually an underwater mountain (identified and named after himself by a skipper in 1880) with a 12–15-foot elevation at low tide and -three feet at high tide. It is easily the largest and deadliest obstacle in Lynn Canal, roughly the size of a small sporting field, and was well-flagged in the daytime, not yet lighted, but hard to see on clear nights and invisible during a raging blizzard (which it was on the nights of October 24–25). Since the ship’s log was lost, we have nothing but ear-witnesses to confirm the Sophia was running wide open at 11–12 knots in those conditions. Several captains of smaller vessels were hunkering down in sheltered harbours that miserable cold, snowy night and could hear the Sophia‘s foghorn making soundings against the mountains on both sides of the fjord. This was common enough for night travel, in those days, but unusual in a blizzard. CPR’s own operations manual cautioned captains against trying to keep to the schedule or make up time in bad weather, but Captain Locke was maintaining a high max speed while running blind. Nobody knows why. The canal is six miles wide at that point, with three miles of deep channel on the east side of Vanderbilt and two more to the west. It was generally believed, afterwards, that either Locke miscalculated his foghorn soundings, misread his last shoreline radio-beacon bearing or was pushed by the powerful North Wind off course, because he landed directly on top of the only well-known obstacle in his way. That was his first inexcusable mistake.

The second was sending home all the rescue vessels from Juneau, just as it was getting to be late afternoon on the 25th. He felt it was unsafe to attempt an evacuation under blizzard conditions and instructed all the rescuers to return early in the morning if the weather was better.What happened in-between was that the rising high tide lifted the bow of the ship off the reef and the strong winds pushed it in a 180-degree pivot, which ripped the double hull to shreds.

She slipped off the reef top and sunk so quickly there was barely time for a final distress call, and over 100 passengers and crew were still in their beds when she went down. There was a large explosion in the boiler room when the water poured in, which speeded up the sinking.

Locke had felt certain the ship would not be moved by the high tide, but he was wrong. What irony when you consider that the definition of Sophia, a Greek derivative, is “divine wisdom.”

The Cold Recovery

The Princess Alice, a CPR sister ship, was given the onerous task of locating and bagging the bodies, the gruesome details of which are well-documented but won’t be related here, except to report she later arrived in Vancouver with 156 bodies at 11 p.m. on November 11, Armistice Day, and was called the “Ship of Sorrow.”

Relatives were identifying and claiming bodies from the Sophia in the midst of “Victory!” celebrations to conclude that hideous first world war.

The Cold Aftermath

It’s been theorized by historians and others that the sinking of the Sophia passed almost unnoticed on the world stage because of this unfortunate timing coincidence with the end of the war, even though it was the biggest maritime disaster ever on the west coast of North America. And that is certainly true.

But there is also no question that it was the biggest disaster in the history of the Yukon and Alaska, dwarfing the 1964 Alaska 9.2 earthquake, which caused only 139 fatalities including various tsunamis in distant places like California.

The world may not have noticed, but northerners certainly did. And we will be noticing again on those three ominous October dates in 2018, 23–24–25, not to celebrate them but to simply be aware that exactly 100 years have passed since “The Northland’s Biggest Disaster.”

The proper mood is genuine heartfelt sadness, with a large dose of melancholia, because it never should have happened. Yet it did.

Amen and RIP to the unfortunate northern pioneers and visitors who met their demise that fateful evening, on top of Vanderbilt Mountain, in the middle of Lynn Canal.

They are long gone, now, but their memories will go on forever, along with “the Lady that’s known as Lou” who once comforted a dying Dangerous Dan McGrew.

Primary sources:

1. The Skaguay Alaskan 2018 tourist edition

2. The new Princess Sophia exhibit in the Skagway Museum, which contains digital bios on all of the victims.

3. The Sophia wall exhibit at the Yukon Transportation Museum, up near the airport in Whitehorse

4. The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North Down With Her, by Ken Coates and Bill Morrison, first printed in 1991, which remains the definitive and thorough study of this tragic disaster and aftermath.

5. The 2018 Alaska State Library Travelling Exhibit: [email protected] or princesssophia.org