Bear!” I exclaim as I’m driving down the road.

After pulling over and stopping for a moment to snap a pic (from inside the car, of course), I continue on my way. One of my favourite things about living in the Yukon is just how familiar an experience this is. Animal viewing is one of the Yukon’s favourite pastimes, and even though I’ve seen bears, moose and other amazing creatures, it’s still always thrilling to see such majestic wildlife.

Wildlife can mean slightly different things depending on where you look. For me, wildlife ranges from the tiniest of ticks found on elk to behemoth bowheads off the Yukon’s north shore. It includes fireweed, aspen, and the photogenic prairie crocus that floods our social media feeds every spring. Wildlife is for me, anything that is wild and is alive, so all the flora and fauna found in the territory.

According to the Yukon Wildlife Act, “wildlife” is defined as only vertebrate animals, excluding fish. As a quick flashback to high school biology, vertebrates are all those animals with backbones: birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and so on.So why does it matter what the definition of “wildlife” is in the Yukon’s laws? It’s important because this definition applies to only a specific group of animals. For plants, insects, and fish we have to look elsewhere.

That’s where ‘Species At Risk’ comes up. Canada passed legislation called the Species At Risk Act in 2002 which provides legal protections for species deemed at risk and works together with existing legislation, like the Yukon Wildlife Act.

A recent study by the Nature Conservancy of Canada found that there are at least 308 species of plants and animals that only exist in Canada. That means that if they were to go extinct here, they would cease to exist completely. Forty three of those species are here in the Yukon, with almost half of those existing only here. The Yukon, together with BC, Alberta & Quebec, is considered one of Canada’s “hot spots” for unique wildlife.

And so, with all the work being done to better understand Canada’s biodiversity, ‘Species At Risk’ has become a common phrase that refers to any species whose population has dropped so low that it needs help recovering, or any species whose population is on its way to these dangerously low levels. An expert-led committee called the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) reviews ecological information and Indigenous knowledge on different species across Canada and groups them into the following categories:

- Not At Risk

- Special Concern

- Threatened

- Endangered

- Extirpated (extinct locally)

- Extinct (globally)

So where do bears rank on this scale? Black bears (like the one I saw last week) are listed as “Not At Risk” meaning they are generally secure in their population. Grizzly bears, however, are listed as “Special Concern.” The Government of Yukon addressed this by creating a conservation plan for grizzly bears in Yukon, which was released in October 2019.

A key component of the Species At Risk Act and the Wildlife Act is having accurate population information. Many biologists are interested in gathering information, especially with population trends being affected by human activity, climate change, and introduction of invasive species. Baseline data is crucial, but can be difficult to obtain. That’s where community science can help. Currently, a local scientist, Lucile Fressigné is working on a community science project to get updated bear population numbers. Her work revolves around analyzing bear scat in certain areas in and around Whitehorse. You can learn about the project and pick up a test kit at the CPAWS office if you’re interested in participating.

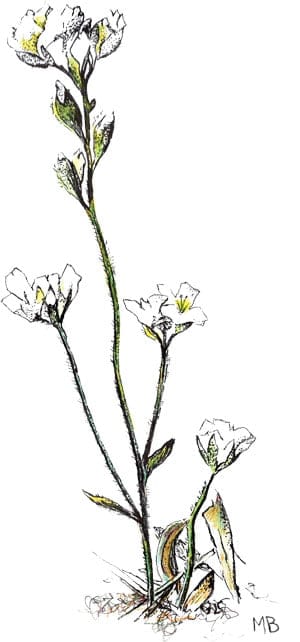

We also spoke a little about community science with our Yukon Spring Nature Challenge. With over 6000 observations catalogued across the territory, this kind of data can help scientists check for trends in population numbers and distributions. It’s also cool to see observations of uncommon or rare species. For example, the flowering plant Yukon Draba (Special Concern) was observed twice as well as a few Barn Swallows (Threatened), and some Transverse Lady Beetles (Special Concern). These observations help add to the foundation of information to help us make informed decisions about the environment around us.

Much of the work done to catalogue the Yukon’s species is done by the Yukon Conservation Data Centre. They work together, analyze and share information on the Yukon’s plants, animals, fungi, and ecosystems at large. Every year they host what’s known as a BioBlitz. It’s usually a weekend-long sprint where biologists and members of the public go into a particular area and gather data about as many species as they can. This year’s BioBlitz was between July 8th – July 10th, at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. Results and information usually take a bit of time to compile, but there is always a great presentation at the annual Yukon Biodiversity Forum on the outcomes of each year’s BioBlitz. I highly recommend keeping an eye out for next year’s forum.

Overall, we’re quite lucky to have apparently stable populations of many iconic Yukon species. Species at risk are something that we will have to continue to see the world change drastically around us. Having a good understanding of population numbers, working on creating and implementing recovery plans for species that are in decline, and staying in touch with the environment around us will go a long way in ensuring we avoid any grisly situations.

Want to learn more about Species At Risk? We released a report in March 2019 that you can find at cpawsyukon.org/species-at-risk